Resilience manifests itself in so many different forms as an artist. But in thinking about how to approach this lecture I realized that I was in the unique position to share a version of the practicing artist that is not yet widely discussed outside of creative circles, aptly named the artist innovator. After working closely with physicists and other scientific professionals for the past several years, I have become deeply passionate about this notion. The term “artist innovator” illustrates the fluidity with which so many artists today construct their practices.

We are individuals that bring a unique perspective to the world. We are translators, interpreters, visionaries, whatever you want to call it, we are curious about the world and how it works. It was then a very quick progression to connect this notion with that of the superorganism, a term that I came across last spring for an exhibition at the Muzeum Sztuki Łódź. “Superorganism: The Avant-Garde and The Experience of Nature” was the first in a series of six exhibitions celebrating 100 years of the Avant-Garde in Poland. “Superorganism” is a term taken from natural science that highlights the relationship between individual and collective potential. It is not a plant, nor a fungus, nor an animal, but rather a unified social entity that when banded together, creates a body with extreme potential but alone, the individuals possess no extraordinary ability. First coined in 1789 by geologist James Hutton to reference the synergistic function of the Earth, the term has since grown to represent a broader spectrum of systems, including biological, social, and cybernetic. In walking through this exhibition I found that it didn’t present a singular statement but rather posited a series of questions regarding the life process in time, through our philosophical, biological, social, spiritual, and political realms. The viewer was inspired to reconsider the context of the avant-garde through both human and cosmic landscapes, we were asked to contemplate the power of our organic totality, our superorganism. The artist innovator is the spur for the modern superorganism. By bringing together engineers, scientists, artists, writers, theorists, politicians, people from all walks, backgrounds, and experiences, we create the human superorganism, the body that protects, carries, encourages, and inspires as we move faster and faster into unknowable worlds. And to a certain extent, this is how I would like to approach things today. I would like to lay out a few possibilities, a few ways to think about art and art making today and what that means for the artist and the community at-large. I hope to provide a new perspective with which to think over, one that will ideally inspire you to consider how the projects or questions that you are investigating right now might be changed by including an artist in your conversation.

Today I will use this frame of the superorganism to talk about artists as a body of individuals that by nature, inspire a more collectively resilient body. I will begin with two examples of artworks—a performance and a photographic work—that deal with trauma, power, and the relationship between the individual and the collective. I will then share two examples of how artists have dealt with the idea of human potential directly within the confines of the biological body, specifically in terms of the cyborg. I will close by returning to the idea of the artist innovator, positioning artists as visionaries for new ways of existing in our ever-changing worlds. I will include my own project and will site additional examples of how artists are creating opportunities to both critique new technologies as well as to use them more consciously.

The first I want to share is an early performance work by the artist Marina Abramovic entitled Rhythm O. This piece was first performed in Studio Morra in Naples, Italy in 1974. The performance included a table of 72 items, which included things like a rose, a feather, perfume, honey, bread, grapes, wine, scissors, a scalpel, and a loaded gun. The artist herself was included as a “prop” and a description which read "I am the object," and, "During this period I take full responsibility.” During this six-hour performance, Abramovic stood still while spectators turned into collaborators, some individuals cared for her while others inflicted pain. The artists’ body became a metaphor for the political body. This performance was ultimately ended (not by Abramovic) when one participant took the loaded gun from the table and held it to her head.

This next piece is a composite image of over 72,000 individual images, part of a larger body of work called Tracking Transience by artist Hasan Elahi. In 2002, shortly after the September 11th attacks in New York City, Elahi was picked up by the FBI on suspicions of terrorist activities. Despite being cleared after six months, he continued to have problems with the Department of Homeland Security for years following the incident, which incited what he calls “a project in self-surveillance.” His location is continually tracked and reported to his website where it is available to both the public and the FBI. In relation to this work, Elahi says “the FBI wanted to know everything about me and I’m all about full disclosure.” In this case, the individual body bears trauma inflicted by a more powerful body. The artist flips the position of surveillance— he is at the same time the watcher and the watched.

Here, resilience is something found in the symbiotic relationship between individual and social development, as referenced in the conference statement by French neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik. These works represent the resilience of the individual body when exposed to trauma on the individual and collective scale. When the social body is sick how does the individual body rebound? If the individual body is sick, how can the social body absorb or heal?

As an individual body in a sea of many, one of the unique abilities that artists possess is the capacity to move fluidly between communities and ideas, creating bridges which eventually helps us move together as a more effective, unified force. Take for example the relationship between the fields of science and art. For centuries, art was used as a tool to illustrate and translate phenomena, many times one individual was simultaneously the scientist and the artist, communicating what he or she saw through their lenses or in the lab. In more recent decades, art has become a tool to critique the impact of scientific and technological research, or also a way to explore these innovations in unexpected ways.

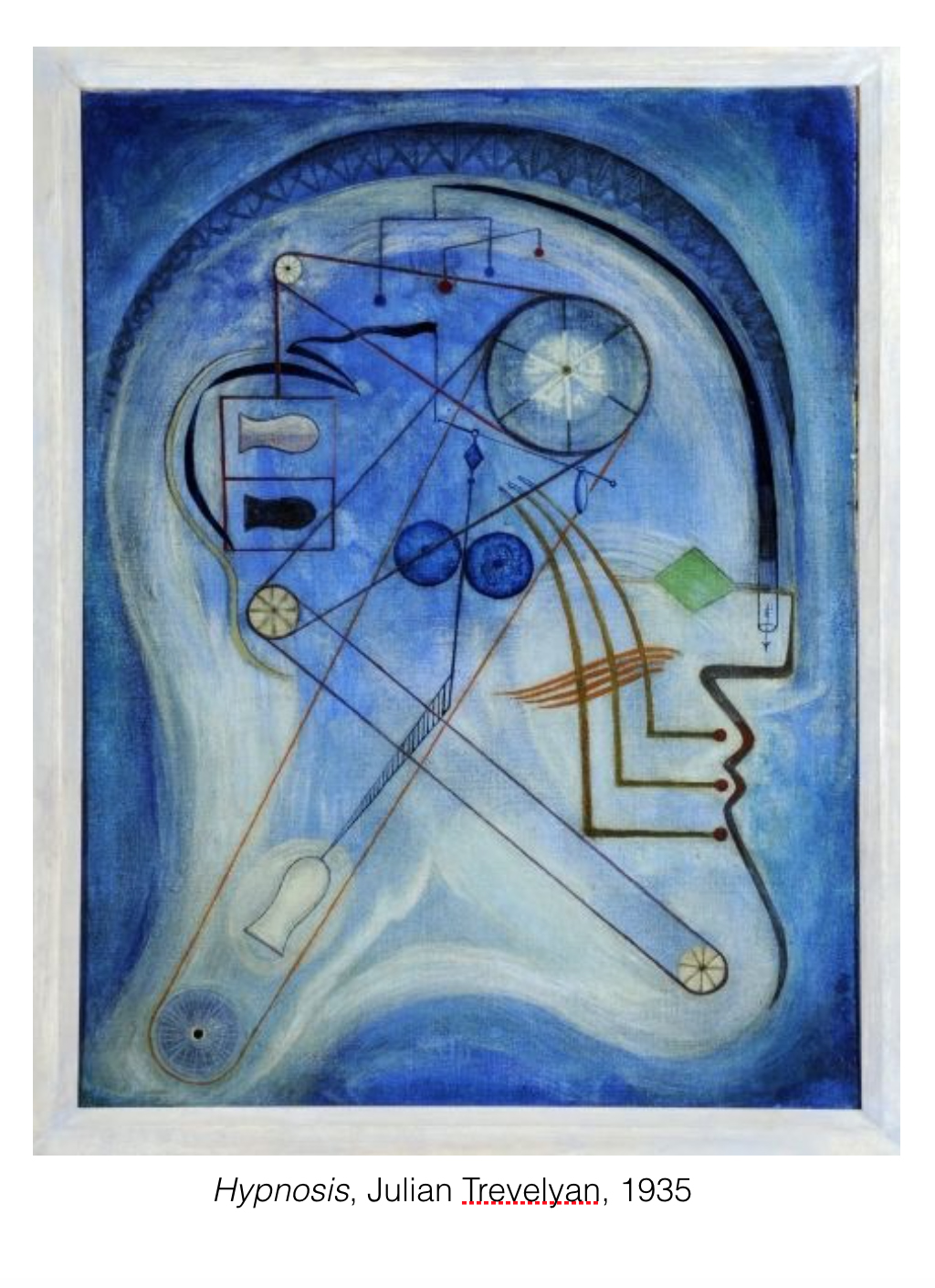

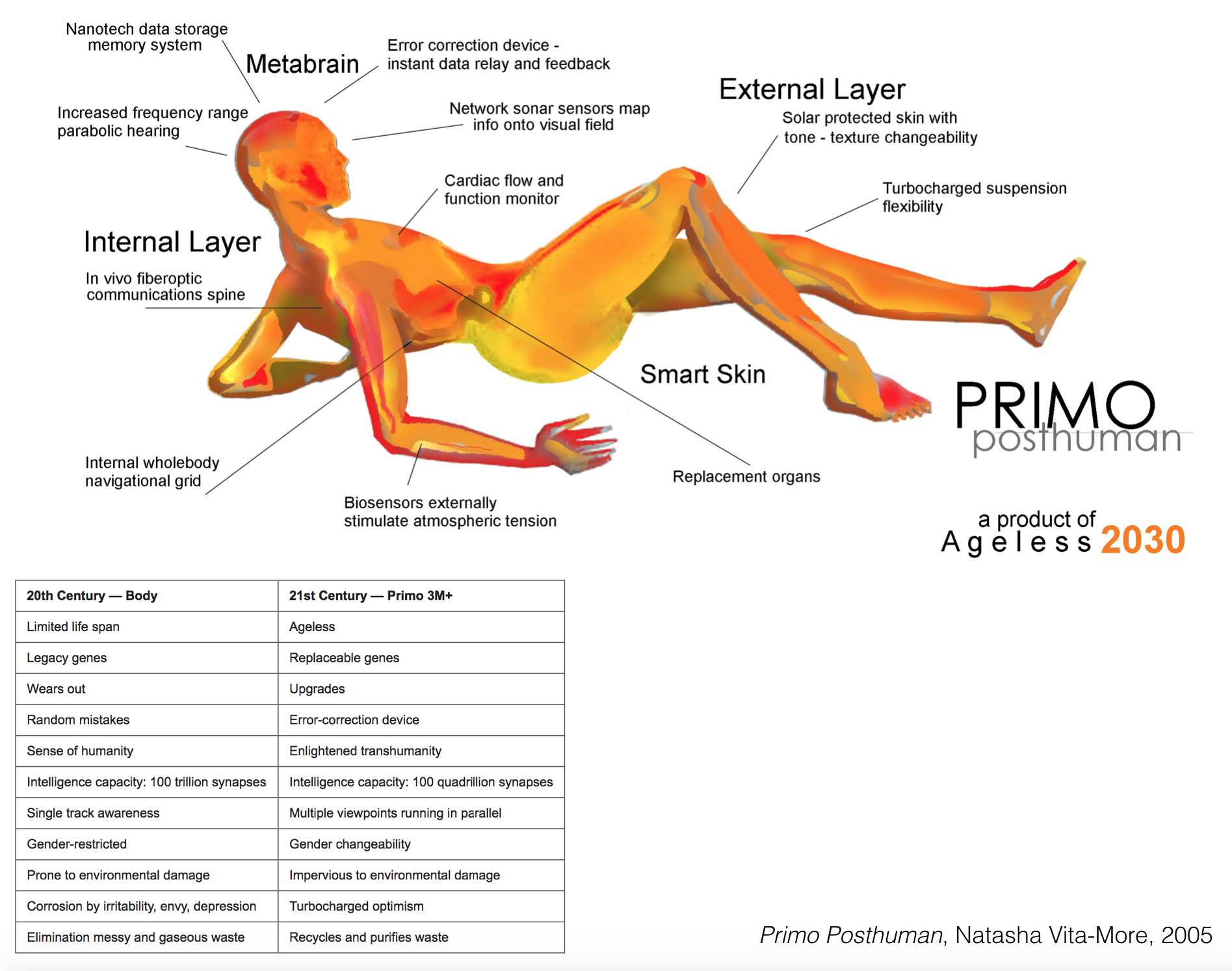

The idea of merging the physiological body with the machine has been a concept since the early 20th century, dealing with the fears about the human body becoming obsolete and the hopes that a synthetic body could help us unlock hidden potentials. Hypnosis, the 1935 painting by British artist Julian Trevelyan depicts the inner mechanics of the brain as it “digests” reality. Trevelyan, who was interested in exploring the multiple levels of human consciousness, envisions the biological body as a mechanical body. The interior space of the mind is the site of mobiles, wheels, belts, and tubes that work together to form a machine-like system that has no obvious start or end point but rather feels as if it works upon its own logic, infinitely. Unsee-able, unknowable potential that is typically locked within the mind is here exposed. The separation between the individual and the collective, the interior space of the mind with the exterior space of the environment is united by the fluid, atmospheric blue color field. Continuing with this notion of potential through the hybrid body, we move into the work of transhumanist theorist Natasha Vita-More. The transhumanist movement, which essentially employs science and technology to evolve the human race beyond our current physical and mental limitations, is a movement that was initiated in the 1920’s. Today it’s not uncommon to think about all of the devices that we use to “optimize” our bodies or the popularity of practices or pills that we hope will unlock some hidden aspects of our minds. Some would even argue that our smartphones have in a way, become our hand-held brains. Primo Posthuman is a project that Vita-More proposed in 2005, she describes it as “the product of intentional design rather than the forces of natural selection. Primo Posthuman is a futuristic version of the human form that’s overcome disease, aging, etc through features like “smart skin” which learns how and when to renew itself and can compute levels of environmental toxins… “Unlike the cyborg, Primo’s unfolding nature is based on expanding choices,” she says, “Unlike the transcendent, Primo is driven by the rational rather than the mystical.” Here, resilience lies in the artists’ ability to work with engineers and technicians to envision and hopefully, eventually, realize, an entirely new way of existing in the world. And while this piece is intended to serve the individual, physical body, its implications for how it could alter all aspects of organic life should not go without mention. Artists like Trevelyan and Vita-More ask us to confront the limitations of our own bodies. Their curiosities, be it about consciousness or tangible, physiological capabilities, help us to envision alternatives to our natural evolutionary paths.

Artists are in the unique position to both be curious about the world and possess the tools to effectively seek their answers. Artists are sensitive to physical and emotional environments and we know how to rapid prototype, or in other words, test out ideas time and time again until we get them right. We are links between the abstract and concrete worlds, and can envision futures while firmly planted in the present. Last fall I created my own initiative based on this idea of the artist innovator and named it The Haptic Mind. I came to Warsaw as a Fulbright Scholar 2.5 years ago to work closely with professionals in the science and business sectors. In this capacity I witnessed first-hand the need for increased communication and empathy in these fields, as well as the effectiveness of interdisciplinary partnerships for inspiring creative problem solving and innovation. The Haptic Mind was born out of my impulse to connect people and ideas, and to use my perspective as a sculptor to solve problems from this unique angle. Another example of an inter- or trans-disciplinary approach, designed to unite various perspectives, is the collective Arts Catalyst, a London-based project that has been actively commissioning and producing projects and artistic works for over 20 years. “We activate new ideas, conversations and transformative experiences across science and culture, engaging people in a dynamic response to our changing world.” One of their most recent initiatives TEST SITES: ASSEMBLY, was an exhibition and supporting program of lectures and workshops that centered on ideas about how we collectively respond to social and environmental challenges. The statement for this exhibition directly refers to the importance of including all levels of voices impacted by events so as to lay “the best path towards resistance and resilience.” One of the workshops conducted in collaboration with this project was called MOLECULAR VIOLENCE, which used the environment to talk about gender discrimination and violence. The website describes the goals of the workshop as “exploring how the "molecular" nature of environmental violence is used to reinforce gender, ethnic, racial, class, or other forms of discrimination, and to find ways for countering this.” Another project, instituted by the Institute for Applied Aesthetics is The Artist Run Space of the Future, which positions the artist-run space (as individual entities and as a network) as a mushroom, its structure echoing that of the rhizomatic structure of fungi— without a beginning or end, the artist-run spaces of the future occupy the non-sites, the non-spaces: storefronts, vacant lots, beaches, places not-before considered the site of art, the site of inquiry, be it cultural or otherwise. This is another concept that I am closely linked to in that I am co-director of Stroboskop, an artist-run space in Warsaw. Together with my partner in the space, Norbert Delman, we have had many conversations about the effectiveness of such spaces and how we can use our tools as artists to realize more for both the local and global communities.

Whether it be physical or digital, collective or individual, resilience in art is the ability to be continually conscious. It is the ability to move fluidly through time and space and category, it is the ability to communicate and connect with people and ideas. It is the ability to work constantly to address the gaps in our research that we probably don’t even have a clue about their existence, it is the ability to continually work beyond any sense of a comfort zone. Resilience is the artists ability to see from the oblique angle and to seek solutions that have not yet been explored. It is our duty to ask questions and be curious, to bring people together and create new models for living in this new world. Because ultimately, the success of the superorganism is predicated on the success of the individuals that create it.